Why I Don’t Like the Word “Dysphoria” is an essay commissioned from actress and Philosophy Tube creator, Abigail Thorn. There is a small content warning here for a casual reference to trans suicide, though nothing graphic or detailed. Abigail asked for her fee to be donated to Alzheimer’s Society, more on that at the end.

There’s a moment in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar when Decius comes to Caesar’s house and summons him before the Senate, only for Caesar to refuse the call. Shocked, Decius says, “Most mighty Caesar let me know some cause, lest I be laughed at when I tell them so!”

Caesar replies: “The cause is in my will. I will not go.”

It’s a revealing moment for Caesar’s character, and I think it also reveals something about the nature of political freedom.

I have Freedom of Movement within my country. That means if I want to go to Bristol, for example, I don’t need permission. If someone stops me and asks why I’m going I don’t have to tell them. I don’t even need a reason, I can go on a whim. It may be that my car won’t start – in that case I am not free in the practical sense. But to have legal and social Freedom of Movement means I am not accountable to anyone else when I attempt to move.

To have this kind of freedom places limits on what authorities may demand of us. No wonder Caesar ruffles so many feathers when he refuses the summons: he puts himself above Rome!

We might apply this lens to sexual consent: if someone refuses to have sex with a potential partner they don’t need a reason beyond the fact that they just don’t want to. Or bodily autonomy: a pregnant person seeking an abortion shouldn’t need a reason – they don’t want to be pregnant anymore and that’s that. Or privacy: I have nothing to hide, but I still don’t want the government reading my emails. We can all be mini-Caesars: the cause is in our will.

I think we can apply it to transition also. Earlier this year I spoke outside Downing Street at a rally condemning the government’s exclusion of trans people from the proposed ban on conversion therapy; I said, “My body does not belong to the state, it does not belong to my parents, it does not belong to God – it belongs to me!” In a happy coincidence, I was wearing earrings shaped like laurel wreaths.

However, our efforts to centre bodily autonomy in stories of transition are stymied by the concept of “gender dysphoria.” I think we would benefit from moving beyond this concept – I think it’s outdated, deeply harmful, and rooted in a philosophical mistake.

The philosopher Gilbert Ryle tells a story about a man who goes to Oxford and sees the colleges and the students and the library and then asks, “Yes but where is the university? You must show me that!” He has made what philosophers call a category error – he thinks “the university” is some extra thing, but it’s just a word for the things he’s seen already.

In the years of denial before I realised I was trans I often thought, “I am jealous of women, especially trans women. I wish I had features X, Y, and Z, and I am sad that I do not, so sad that I often wish I was dead. But I do not have dysphoria.” In hindsight this was a category error: those feelings – jealousy, sadness, wishing – were ‘dysphoria.’

With that in mind, I have some questions. Suppose a cis woman goes through menopause, wakes up one morning and thinks, “Ugh! My body doesn’t feel like my own! I feel anxious and depressed and mannish!” Is that dysphoria? I have combed through forums for people experiencing menopause and the descriptions of the mental discomfort are strikingly similar to those found in trans forums.

If a cis man is short, or skinny, or beardless, and wishes he were “manlier,” is that dysphoria? If a cis woman with a hairy lip thinks, “I look like a man!” is that dysphoria? If she gets electrolysis, breast augmentation surgery, a Brazilian butt lift, or a rhinoplasty, are those “gender affirming procedures”?

I think the only sensible answer is, “Yes! – insofar as the concept of ‘gender dysphoria’ makes sense at all.” As an actress and writer I know the power of using the right words. ‘Envy,’ ‘sadness,’ and ‘yearning’ are all perfectly serviceable.

If the answer is “No,” then why? What is it about these feelings that makes them different when a trans person feels them? What is it about these medical interventions that makes them different when a trans person needs them? Most importantly, why are those treatments so much harder to get for trans people?

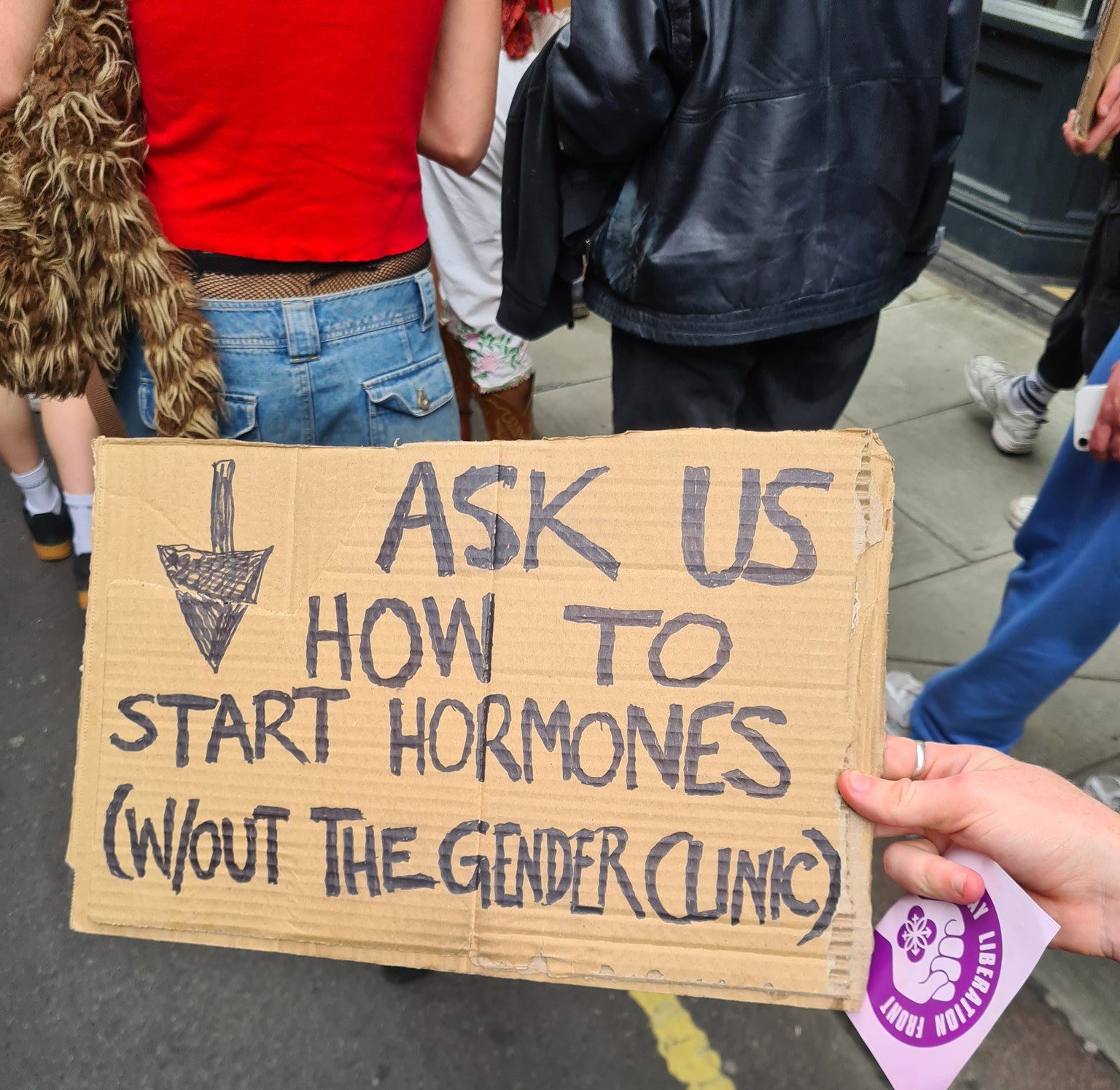

I think it’s important to explore this category error because it’s the root of the NHS’ systemic transphobia. If a cis woman wants breast augmentation to correct uneven or underdeveloped breasts she can present to her GP with “significant psychological distress” and be referred to a plastic surgeon, but only a specialist in a Gender Identity Clinic can diagnose “gender dysphoria.” So a cis woman who wants breast augmentation can be referred to a surgeon by her GP but a trans woman who wants the same procedure from the same surgeon has to go to a segregated clinic to be diagnosed with this extra thing, “dysphoria,” first.

It’s the same across the board: a cis woman going through menopause can get HRT from her GP but a trans woman who wants the same drugs to transition has to go to the segregated clinic. A cis woman who wants breast reduction for back pain can get a referral from her GP; a trans man has to go to the segregated clinic.

(I am aware of course that cis women seeking these interventions often find the NHS to be recalcitrant – GPs may misdiagnose, and Trusts may arbitrarily refuse to fund surgeries. This is consistent with the fact that trans people have to contend both with doctors not following the rules and the system being transphobic.)

The waiting list for Gender Identity Clinics are years long and many of us kill ourselves before being seen. (How’s that for “significant psychological distress!”) However I don’t think the waiting times are the root of the problem. If I’m right that “dysphoria” is a category error then a separate clinical pathway for trans patients is pointless: doctors who look for dysphoria are like the man in Oxford looking for the university.

Even if the waiting time for Gender Identity Clinics was measured in minutes, why do we have to go there when cis people don’t? If the NHS required pregnant people to get a diagnosis of “Pregnancy Aversion Syndrome” from two psychiatrists before they could get an abortion this would be widely understood as an unacceptable violation of their bodily autonomy. “Pregnancy Aversion Syndrome” is an inherently belittling and pathologising idea: it suggests that people who want abortions need a reason outside their will. It denies them the status of human beings who make their own decisions and subtly suggests that remaining pregnant is a moral norm from which abortion is deviant. In the same way, “dysphoria” preserves the power of cis gatekeepers. The root of the problem is that the NHS is segregated.

Not only is “dysphoria” used to segregate care, it’s also used to justify taking it away. Anti-trans campaigners in the UK frame their proposals as alternative treatments for gender dysphoria, pushing “exploratory therapy” (conversion therapy), or “watch and wait” (conversion therapy by default). The concept of “dysphoria” also plays a key role in arguments of the form, “There are some genuine transsexuals, BUT,” which often precedes a call to withdraw healthcare, especially from trans children. (e.g. “There are some genuinely dysphoric transsexuals BUT these days kids get rushed into it by big pharma!”) In the USA, Florida’s recent attempt to take gender affirming care from recipients of Medicaid was justified by a report claiming that it is ineffective at treating dysphoria. “Dysphoria” allows transition to be framed as just another medical need, one that might be “better treated” by stamping it out. It also conveniently ignores the fact that our distress is often caused by cis people’s stigmatisation of our desires, rather than the desires themselves.

I would prefer to centre desire and will when talking about transition. To me, transition is more than meeting a medical need, just like crossing the Rubicon was more than Caesar getting his feet wet. It’s taking your life in your hands and shaping it yourself. I think that’s beautiful. I didn’t transition to “alleviate my dysphoria,” I transitioned because I fucking wanted to. Who is the state, or a doctor, to tell me I can’t?

All this talk of willpower and Roman glory might sound very individualistic but I think centering desire in transition has radical potential. Anti-trans campaigners don’t want “more effective treatment for dysphoria”; they want the government to control what individuals may do with their own bodies because the truth that trans people represent – that sex is neither binary nor immutable – means sexual heirarchies are malleable human constructions. In this way we can see the anti-gender movement for the deeply patriarchal, deeply misogynistic, and fundamentally fascist crusade that it is. Why let them hide this abhorrent political ideology behind sanitised medical language?

As writer Shon Faye says in her book The Transgender Issue:

“Trans people are emblematic of wider, conceptual concerns about the autonomy of the individual in society. Their rejection of dominant, ancient and deep-seated ideas about the connection between biological characteristics and identity causes a dilemma for the nation state: whether to acknowledge and give credence to the individual’s assertion of their own identity in law and in culture; or to mandate that it, the state, is the final authority on identity, and to assert its power over the individual – by force if necessary.”

I know not all trans people share my feelings on this. Some believe they need to use the language cis people expect, so they say “dysphoria” as a matter of realpolitik. Others say being invited to reframe their experiences feels like being invalidated. I use “dysphoria” myself sometimes as a shorthand for, “I feel sad about the distance between what I want and what I have.” It must also be acknowledged that ‘dysphoric’ is at least better than ‘autogynephilic’ or ‘degenerate.’

But centering the desire to transition centres our agency as human beings. It puts cisnormative systems of government and administration on the back foot – demanding that they justify the things they put us through.

The cause is in my will.